It is nearly 25 years since the Good Friday Agreement came into effect, which officially marked the end of ‘The Troubles’, which lasted 30 years (1968 – 1998). It was a period of deadly conflict between those who were advocating Irish unity (the Nationalists/Republicans) and those who wished for the six counties of Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom (the Unionists/Loyalists). During that period, it is fair to say that Northern Ireland was not considered a significant tourist destination, not least because it was often perceived as unsafe. For example, the Europa Hotel, Belfast’s most prestigious hotel, was bombed 36 times during ‘The Troubles’.

Northern Ireland is now enjoying a mini tourist boom, stimulated in part by its natural beauty (e.g. the Giants Causeway) which featured prominently in the hugely popular television series, Game of Thrones, and also via significant investment in tourism infrastructure and attractions, not least the Titanic Museum in Belfast.

It is an impressive immersive museum providing excellent social and historical context, although some might feel its fate is symbolic of the British shipbuilding industry. Just in sight of the museum is Harland and Wolff, one of the last active shipyards in Britain, and the company which built the Titanic. Unfortunately, its days look numbered. Its huge yellow gantries dominate the Belfast harbour area.

In visiting Belfast and Derry, what was particularly intriguing was the (dark) tourism relating to the city landmarks and neighbourhoods which were the site of many of the confrontations and violent incidents during ‘The Troubles’.

Belfast Murals

The conflict in Northern Ireland during the early phase of the late 1960s – early 1970s tended to cause minority groups in mixed working class areas of Belfast to flee their houses – an example of what nowadays might be called ‘ethnic cleansing’. This often led to almost homogeneous Protestant and Catholic neighbourhoods, which were kept apart initially by barriers, and then walls, many of which still exist today. Perhaps the most well known is the so called ‘Peace Wall’ which divides the largely Protestant Shanklin Road area from the largely Catholic Falls Road area.

Each of the two areas contain numerous striking murals which reflect not only the political views and historical experiences of the local people, but also often address current issues and grievances

The Falls Road

Probably the most famous mural here is that depicting Bobby Sands, the IRA hunger striker who starved himself to death in 1981

A month before he died, he had been elected to the British Parliament in a by-election whilst standing as a ‘political prisoner’. His electoral success helped pave the way for a new political strategy of victory via the ballot box through Sinn Fein, the political wing of the IRA. In the most recent UK General Election of 2024, Sinn Fein became Northern Ireland’s largest party in Westminster, having already become the biggest party in the Northern Ireland Assembly in Stormont.

Given the rise in the number of tourists/visitors to the area, it is not surprising that some of the murals are aimed at providing some historical context from the Republican perspective.

It’s also possible to take away some souvenirs and mementos

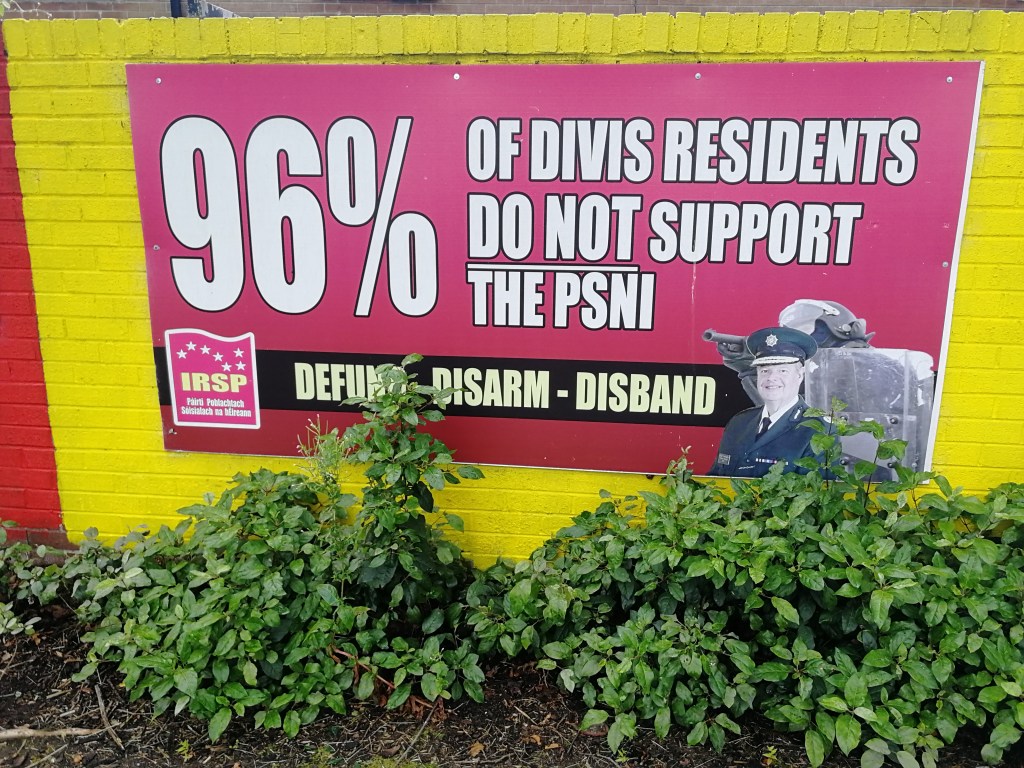

However, it would be a mistake to think there is not some lingering tension and mistrust. We witnessed first hand the presence of a member of the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) creeping along side an anti-police poster

At the time of our visit, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was very intense, and there was considerable evidence that the Northern Irish Republicans very much identify with the plight of the Palestinians, especially in occupied Gaza

Shankill Road

The Shankhill is the most renowned Loyalist area of Belfast. Both the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), the leading loyalist para-military organisations during The Troubles, originated in the area. At its heart is the Shankhill Road. Along its route can be seen numerous murals which celebrate the Union between Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom, as well as the associated loyalty to the Crown.

Many of the murals celebrate specific historical landmarks and cultural traditions which are still honored today, such as the Orange Order parade which occurs during the ‘marching season’ between April and August.

As in the Falls Road, there is an attempt to provide a Unionist interpretation of some of the more controversial episodes of the Troubles, which includes making comparisons between IRA ‘atrocities’ and those of ISIS and Islamic terrorism.

The Shankill Road now forms part of the Belfast tourist bus route, a far cry from during ‘The Troubles’ when it was considered a dangerous place for outsiders to visit.

Whilst the old terraced housing has been largely replaced by new estates, the Shankhill is still one of the most deprived areas of Northern Ireland, and has suffered a sharp decline in population in recent decades.

Unionist loyalties can be seen in other areas of the city such as South Belfast

Other murals pay homage to local sporting heroes such as snooker star Alex Higgins and footballing legend George Best (who was born in East Belfast)

Derry/Londonderry

The two differing names for the same city amply symbolise the historical divide between Republican and Unionist political allegiances in Northern Ireland. At the beginning of the 17th century, settlers began arriving, largely from Scotland and Northern England, a colonial episode known as the Plantation. The process was overseen by London guilds, as reflected in the stained glass windows of Derry’s Guild Hall.

It was in Derry, Northern Ireland’s second largest city, that arguably ‘The Troubles’ began in the late 1960s during and after the Civil Rights marches. These protests were aimed at challenging the social and political discrimination against the city’s (majority) Catholic citizens by the minority (Protestant controlled) institutions of local government and law enforcement. In August 1969, violence broke out between residents of Derry’s Bogside district and Unionist participants in the Apprentice Boys march. The deployment and heavy handed tactics of the notorious Protestant dominated Ulster Special Constabulary (USC), known as the B Specials, contributed to what became known as the ‘Battle of the Bogside‘.

Later in 1969, the British Army took over from the USC (who were disbanded a year later). Whilst initially welcomed by the local population, relations quickly turned sour and reached their nadir in 1972 following ‘Bloody Sunday’, probably the most infamous incident during the whole of the ‘the Troubles’

Nowadays, the Bogside is home to numerous striking political murals as well as the Museum of Free Derry

Whist the Protestant population in Derry has steadily declined in number, there are still areas of the city where you can see its Unionist allegiances.

In small black print, someone has written ‘Support Soldier F’. This refers to the one British soldier who has been charged with two of the Bloody Sunday killings, and who finally appeared in court in June 2024, over 52 years after the incident occurred.

Two murals from the Waterside area of Derry near the Erbington Barracks where the British Army was based during the Troubles.

Notwithstanding its troubled political history and continuing problems of poverty and deprivation, we found Derry to be an extremely friendly and attractive city – not least its circuit of historic walls. One of the city’s newer murals pays tribute to Derry Girls, the successful tv comedy series, whilst another highlights a popular long standing Italian restaurant